Marvelous Monarchs: The Remarkable Migration of the Monarch Butterfly

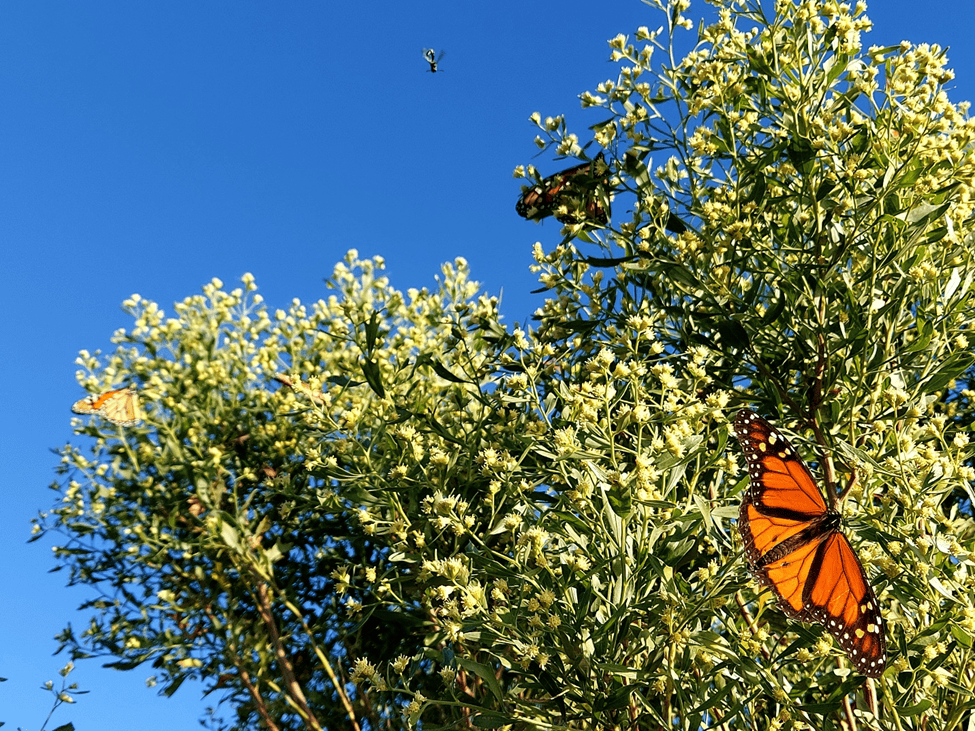

Maybe you have noticed it: the flash of brilliant orange wings flitting by before gently alighting on a nearby nectar bush.

This is a sign that monarch butterflies are on the move. As they make their massive fall migration south, you may spot them in Southeast Georgia. Below, learn more about these delicate insects and their incredible journey.

Bitter Butterflies

Monarch butterflies, which are found across North America, are iconic for their distinctive deep orange coloring with black veining and bodies. This acts as a “Don’t Eat Me” sign, alerting predators the insect is poisonous. Monarchs’ toxicity comes from milkweed, the caterpillars’ only food source. As they feed, the caterpillars store up toxins in their body, which remain in their system even into adulthood. Although an animal which eats a monarch butterfly usually does not die, it feels sick enough to avoid eating them in the future.

Most adult monarchs only live a few weeks as they search for food in the form of flower nectar, for mates, and for milkweed on which to lay their eggs. The last generation to hatch in late summer delays sexual maturity – living as long as eight months – to undertake a spectacular fall migration, one of the few insects to do so.

Monarchs’ Great Migration

From September to early October, millions of these insects begin their southerly fall migration from as far north as southern Canada. Monarchs in the east travel down the Atlantic coast, with many stopping at Florida’s Panhandle (St. Mark’s National Wildlife Refuge in this area is optimal for viewing migrating monarchs, as they are attracted to its saltbushes). They then fly over the Gulf Coast to central Mexico, nearly 2,500 miles from their starting point. Some estimates say up to a billion butterflies arrive in Mexico each year.

There in the fir forests of Mexico’s mountains, they hibernate for the winter in sheltered sites, particularly on trees, where they cluster on trunks and big branches. These international travelers return to the same forests each year, and some even find the same tree their ancestors landed on.

Around March when northerly migration commences, monarchs in Mexico become sexually mature and mate. The males then die, while the females head north, depositing eggs on milkweed plants along the way. These females eventually die themselves, and their offspring continue the northward migration. It takes three to five generations to repopulate the United States and southern Canada. Finally, the last generation of the year hatches and begins the return journey to overwintering grounds in Mexico.

How We Can Help

A single monarch can travel hundreds or even thousands of miles. The recapture of marked butterflies has revealed they can travel as far as eighty miles in one day. The longest distance recorded for the complete flight of a single migrant monarch butterfly is 1,870 miles.

Although scientists believe North American monarchs have been making their remarkable annual journey for thousands of years, threats to their habitat and food sources are making this migration more difficult. Habitat destruction in areas where they spend the winter has taken a massive toll. In their summer habitats, herbicides kill both native nectar plants where adult monarchs feed as well as the milkweed their caterpillars need as host plants. Insecticides kill the monarchs themselves. Since the 1990s, the monarch population has declined by approximately ninety percent, placing them on the endangered species list.

How can you help? Plant pesticide-free native milkweed in your yard so that monarch butterflies can lay their eggs and caterpillars have food to eat. The species of milkweed native to southeast Georgia is “Largeflower Milkweed,” or Asclepias connivens. Planting locally native species is the best way to help monarchs; the butterflies have coevolved with native plants, and their life cycles are in sync with each other. Visit the National Wildlife Federation to find other plants native to our area and the wildlife they support.

Monarchs: A Miracle of Nature

The monarch butterfly’s migration is one of the greatest phenomena in the natural world. Scientists still are not sure how migrating monarchs know where to go when each individual has never made the journey before. How remarkable that these beautiful insects participate in a process which they will never see to completion! Their inspiring journey makes me realize that worthwhile results take time, patience, and hard work. What lesson does it teach you?

Learn more about Southeast Georgia’s nature, culture, and history on one of our tours!

Check out our Cumberland Island Walking Tour: Haunting Ruins and Wild Horses or ourSt. Marys Murder, Mayhem, and Martinis Walking Tour!