Horsing Around: Cumberland Island’s Wild Horses and Their Social Structure

We are now in the midst of spring, when the azaleas flaunt their bright colors, the trees resprout their neon-green leaves, and the marshes’ cordgrass gain new life. It is a time of rebirth.

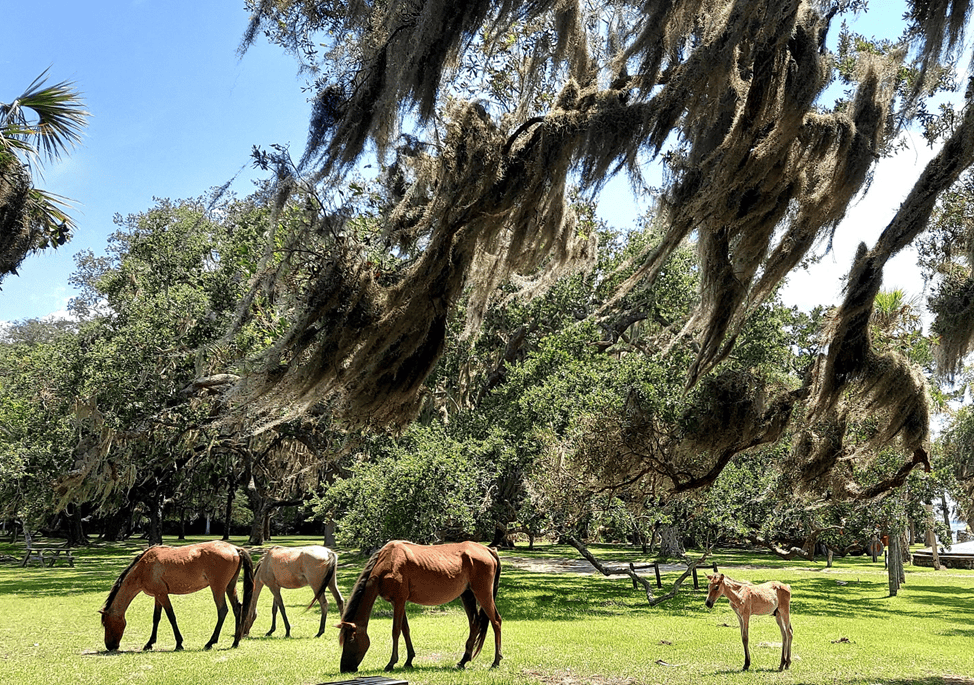

On Cumberland Island, it is also a time of birth, with foals’ being born to the island’s wild horses. As new numbers are added to their ranks, the horses’ social dynamics inevitably change. Let us study these creatures’ fascinating behaviors here.

Herd Mentality

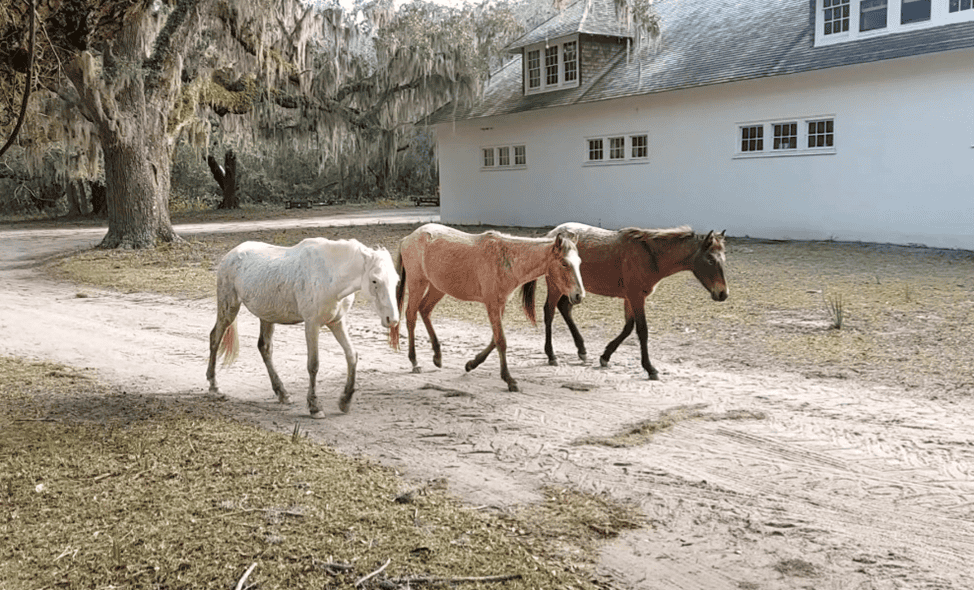

Horses are a social species and choose to live in groups, where there are rules governing their relationships and interactions. Cumberland Island’s 150 wild horses are divided into smaller groups, called harems, which are composed of an alpha stallion, sometimes a beta stallion, mares, and their young.

The alpha stallion is the herd’s guardian. He acts as coordinator of the herd, keeping the females and their offspring together and following behind the group when it moves, ready to protect them from other stallions if necessary. The more dominant the stallion (the higher on the hierarchy he is), the less he fears threats from other stallions and the less he must herd his mares.

Mama Knows Best

The core of the harem is the mares, which stay together even if the stallion leaves or dies. Although the alpha stallion owns the herd, the alpha mare is the herd’s leader. Usually the oldest mare and daughter or granddaughter of other alpha mares, she knows the routes and terrain the herd travels, its potential hazards, and the location and quality of resources. She will make decisions that affect the survival of the herd, such as when it is safe to move on or to drink.

There are strong family bonds within the group, especially between mares and their foals. Upon reaching sexual maturity around two years of age, fillies may remain in their natural herd, join an already-existing herd, or form a new one with a bachelor stallion. Two-year-old colts also leave the group, stay alone for a few months, and then may form a “bachelor band” with up to 16 males. Later they may join a different group or establish a new one.

Who’s the Alpha?

Each time horses meet, there is some kind of interaction. Every interaction answers the question, “Who is dominant?” Usually, the horse which wins more conflicts is more dominant and gets his or her choice of feed, the first chance for water, and the opportunity to pass on genes.

Some interactions can be very subtle, such as stallions’ simply looking at each other, but encounters may become quite violent, with stallions’ standing on their hind legs and biting at each other’s jugular veins. While disputes could occur over a grazing area, a water hole, or mares, the highest escalations occur over fertile mares. However, horses avoid aggressive encounters whenever possible, as they use up valuable energy, present risks in terms of health and injury, and weaken the cohesion of the group.

The result of any interaction is usually a clear winner and loser. A stallion which loses does not necessarily run away; he may suddenly be interested in grazing or may walk to his mares and move them away to protect them. This hierarchy is a natural part of horse life.

Let’s Talk About It

Horses have a variety of vocal and non-vocal communication. Vocal noises include squeals or screams, which usually denote a threat by a stallion or mare. Nickers are low-pitched and quiet; a stallion will nicker when courting a mare, and a mare and foal nicker to each other. Neighs or whinnies let other horses know where they are. They can respond to each other’s whinnies even when out of sight. Blowing – a strong, rapid expulsion of air – is usually a sign of alarm used to warn others.

Conclusion

While it is delightful to observe Cumberland’s wild horses grazing peacefully against the dramatic backdrop of the Dungeness Ruins, it is even more enjoyable when armed with a better understanding of their social structure and interactions. The next time we visit the island, perhaps we will be able to interpret their behaviors that previously seemed mysterious to us.

Want to learn more about Cumberland Island’s horses and even see them for yourself? Then join us on our Cumberland Island Walking Tour: Haunting Ruins and Wild Horses!