The Knobbed Whelk: The Pride of Georgia

Summer is here, which means slow, relaxing days at the beach. Storm season, too, has arrived, resulting in plenty of shells washing onto our beaches and making for rewarding beach combing. A particularly prized shell is the elegant knobbed whelk, but did you know it has a deeper significance to Georgians than any other shell? It is, in fact, Georgia’s state shell. Below, learn more about the knobbed whelk, its background, and its connection to Georgia.

Knobbed whelks (not to be confused with conch shells) are marine gastropods, of the same family with slugs and snails. They grow to between five and nine inches in length and can live up to 40 years. These creatures live in coastal waters and tidal estuaries along the Atlantic coast from Cape Cod, Massachusetts, to Cape Canaveral, Florida, and are common along Georgia’s seashore.

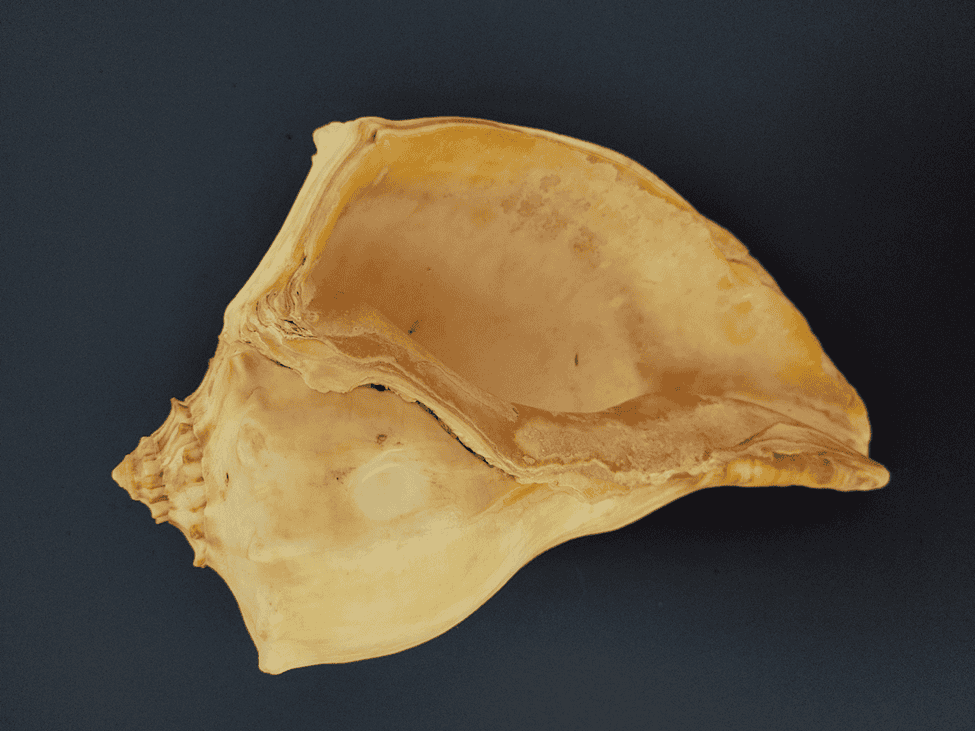

The whelk’s shell is covered with triangular knobs or bumps on its shoulder, giving it the name “knobbed.” The very top peak of its shell is where the whelk began; it then creates turns (known as whorls) as it grows. The final whorl, or body whorl, is the largest and creates the opening into which the snail retreats. A hard lid, called the operculum, acts as a trap door to shut the snail inside for safety.

Whelks are carnivores and mainly feed on worms, clams, mussels, other snails, and even dead organisms. They use a muscular foot which emerges from their shell, as well as the shell itself, to chip at and pry open hard clams and oysters. They then tear away strips of their victims’ tissue and consume them.

If that feeding strategy does not work, a hungry whelk uses an acidic secretion to soften its prey’s shell and then drill a hole with its radula, or tiny teeth, to suck the juice and soft meat from inside a victim’s exoskeleton. This is why we see many shells with a tiny circular hole, which people often use to turn the shells into necklaces.

Scientists surmise knobbed whelks are protandric hermaphrodites, meaning they begin their lives as males and transform into females as they mature. Female whelks lay eggs twice a year, in the spring and fall. Their long, spiral-shaped strings of egg cases, each holding about 100 tiny eggs, can reach lengths of up to one foot. These egg cases often wash up on beaches from the ocean so that beach combers may find them on shore. Each snail which emerges from an egg case is born with a shell, and it takes three to five years for this young whelk to reach maturity.

Knobbed whelks are important to the environment for several reasons: hermit crabs and small or juvenile fish use whelk shells to protect themselves from predators; algae, sea grass, and sponges cling to their shells for support; and finally, their shells, made mostly of calcium carbonate, dissolve slowly to recycle chemicals back into the ocean and help slow down ocean acidification.

Although “whelking,” or fishing for whelk, is not a major industry in Georgia, there is a demand for its meat for those who enjoy it in chowders, fritters, and other dishes. The whelking season runs from the beginning of January to the end of March, when heavy trawling nets scoop up these creatures from the ocean floor.

It is difficult to estimate the number of knobbed whelks left, since their conservation status is not closely monitored. However, it is assumed that many species of whelks are not endangered or nearing extinction since commercial fishing for these snails is still fruitful.

In 1987, the Georgia General Assembly designated the knobbed whelk as the state’s official shell, hoping to “encourage citizens…and visitors alike to visit the beautiful beaches and coastal waters of the state.” It is one of only fourteen states to claim a state shell.

Whether the knobbed whelk’s status as Georgia’s official shell has increased visitation to our state or not, we can appreciate the fact that this prized shell is “ours.” If we find it for ourselves on Cumberland Island or another favorite beach, let us value it even more now that we know it is not just a pretty face!

Learn more about Cumberland Island, its history, and ecology on our Cumberland Island Walking Tour: Haunting Ruins and Wild Horses!