5 Reasons Why the American Southeast Doesn’t Habla Espanol

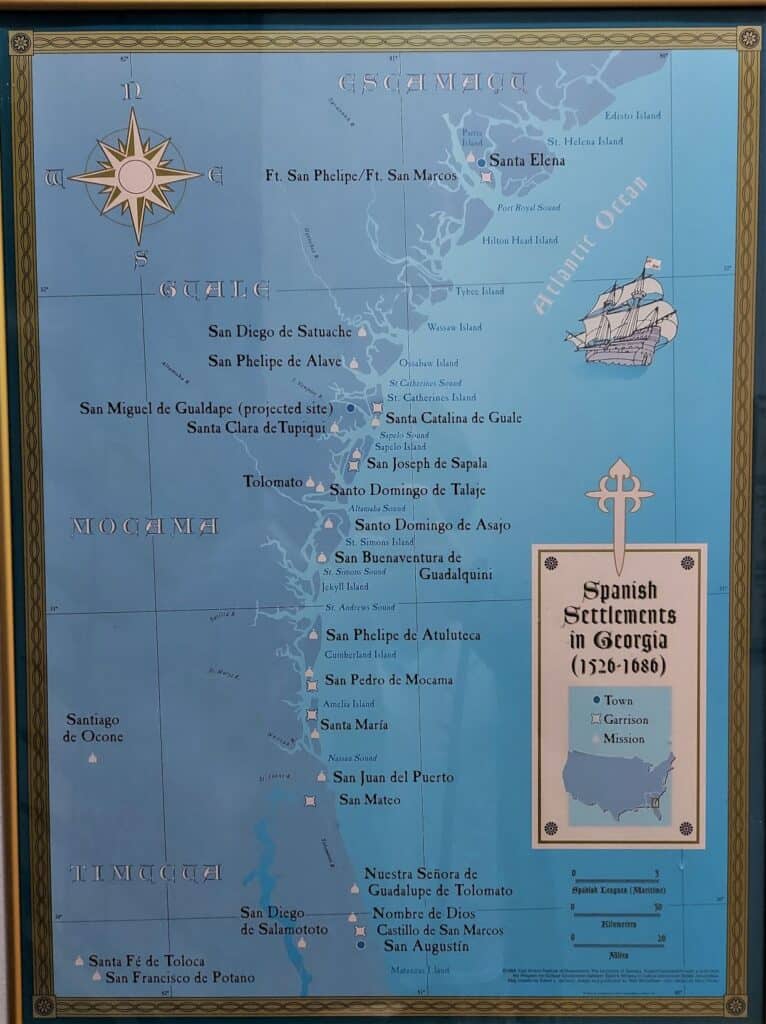

San Miguel de Gualdape, Sapelo Sound, Georgia, 1526.

Santa Elena, Parris Island, South Carolina, 1566.

Trading Ford (in present-day Salisbury), North Carolina, 1567.

Spanish forts and settlements such as these dotted the American Southeast from North Carolina to Louisiana long before the British arrived. By the late 1500s, Spain’s power over this area was unquestioned, but within a few years it had lost almost all of its Southeastern holdings.

Why? The simple answer: Poor planning and poorer social skills. Here are the details:

1. Pass the Plate

Spanish soldiers’ demands for food triggered Native American hostilities. This was a problem especially at Fort San Juan near present-day Morganton, North Carolina. While at first the fort’s founder, Juan Pardo, succeeded in developing favorable relationships with the nearby Mississippi people by offering gifts of European goods such as beads, cloth, and iron tools, Spanish soldiers’ demands for food soon placed an unsustainable burden on native communities. By 1568, one year after the Spanish established this base, the native people turned against Pardo’s garrisons, killing all but one of his 120 men and burning down all six Spanish forts in the area. This event halted Spanish efforts to colonize the interior of North Carolina.

2. Ladies’ Men…Or Not

The Spanish soldiers lusted after Native American women which (surprise, surprise) complicated the relationship between these two peoples. One Catawba chief offered a solution in 1701: whenever European visitors entered his settlement, the chief would offer them indigenous women he kept as prostitutes. I would imagine this arrangement did not work out too well, either!

3. Check the Calendar

Poor planning sometimes resulted in the starvation and death of the Spanish settlers. For instance, Lucas Vázquez de Ayllón, who established San Miguel de Gualdape on Sapelo Sound in Georgia in 1526 with 600 men, women, and children, built his community too late in the year for his settlers to plant crops, causing them to fall sick and die at a rapid rate. Three months after they established the colony, the remaining settlers began a deadly winter voyage back to Hispaniola (today’s Greater Antilles). Only 150 of the original 600 colonists returned alive.

4. No Pain for the Native Americans, No Gain

The Spanish exploited Native Americans for labor. For example, when Hernando de Soto led an expedition to the American Southeast in search of gold and silver in 1539, he arrived at present-day Tampa Bay with more than 650 men, a few women, and plenty of shackles to enslave Native Americans. He typically took hostages in each town to inform him where he could find treasure and food and to lead him to the next town, and he also seized hundreds of slaves to carry the party’s luggage and supplies. As a result, his men were often trapped and killed in Native American ambushes. After de Soto’s death due to illness along the Mississippi River, the surviving members sailed down the river (many of them killed by Native Americans along the way) before reaching open water and escaping to Mexico.

5. Pick Your Battles

The Habsburg Empire, which was in control of Spain, had overextended itself, as it was often waging war against several other powers in Europe. Funds and soldiers that the empire could have used to assist in the conquest of the American Southeast were directed instead toward European problems, mainly in the Netherlands, where the Spanish waged a decades-long campaign to retain control. They ultimately failed in this, too.

In addition, the English government under Elizabeth I ramped up pressure on Spanish forces in the Southeast, even leading a successful naval assault on St. Augustine under Sir Francis Drake in 1585.

The death knell of the Spaniards’ imperial dreams in the Southeast occurred with a Native American uprising in South Carolina in 1576, forcing the residents of Santa Elena, the Spaniards’ first colonial capital, to flee to St. Augustine. After rebuilding the Carolina fort in 1577, the Spanish decided they lacked enough military might to defend the settlement so they torched it and sailed to St. Augustine for good. Just as their Santa Elena fort, the Spaniards’ aspirations of empire went up in smoke.

Spain did later achieve successes in California and maintained power throughout Latin America for centuries, but in the American Southeast, it eventually controlled only Florida and the Gulf Coast area. The British, with their sharp trading skills, wide-ranging organizational talent, and ability to manipulate the Native Americans by drawing them into the European trading network, allowed them to take firm control where the Spanish could not.

Adios, Espana!

Learn more about the Spanish in Southeast Georgia on our Cumberland Island and St. Marys Walking Tours!