Striking Oil in Southeast Georgia: The Olive

It is that time of year again. The olives are ripening and turning bright green or black. Very soon they will be harvested before being transformed into a deep yellow olive oil.

Maybe you think I am referring to harvesting season in Italy, Spain, or even California, but did you know that Southeast Georgia has its own olive producing industry? In this article, we will delve into the history of olive production in Georgia – including Cumberland Island – and the renaissance it is experiencing today.

Olives are native to the Middle East and Mediterranean basin and probably first arrived in the New World around 1600, when Spanish settlers planted them at missions along the Georgia coast. Georgia founder James Oglethorpe, when he landed at Savannah in 1733, encouraged settlers to grow olives with little success. Thomas Jefferson encountered olives as minister to France and shipped 500 seedlings to Georgia and South Carolina, but they were never planted.

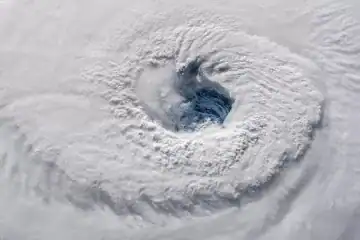

Olives made little headway in the South for several reasons: many varieties simply did not take to the damp climate, hurricanes destroyed others, and the Civil War devastated the coastal plantations that had experimented with the crop. The market played a factor, too. There was not much call for another cooking oil beyond pork fat and cottonseeds (the main component of shortenings like Crisco, short for “crystalized cottonseed oil”).

Although several of Georgia’s Sea Islands possessed olive groves before the Civil War, Cumberland boasts perhaps Georgia’s greatest olive-growing success story. At her 1820s Dungeness plantation, Louisa Greene Shaw, daughter of Nathanael and Catharine Greene, cultivated several hundred olive trees in addition to the Southern staple of cotton. Even into the 1880s, the then-owner of Dungeness, General Mackay Davis, wrote of the presence of 600 olives trees which he claimed still yielded large quantities of fruit.

The next mistress of Dungeness, Lucy Carnegie, brought about the demise of Cumberland’s olive groves. After completing her palatial Dungeness mansion in 1885, she continued to make additions and improvements and in 1896 added a dining room with floors crafted from Louisa’s century-old olive trees.

It was not until the new millennium that olive production in Georgia was revived. Georgians began to investigate the possibility of growing olives in 2000 in part because of a devastating drought, which caused farmers to search for a hardier product. Georgia blueberry growers, too, became intrigued by the prospect of olives because they could use their harvesters to pick this fall crop.

After experimental plantings in 2008, Georgia Olive Farms, a family-run olive grove in Lakeland, harvested in 2011 the first commercial olives east of the Mississippi since the 1800s. Today, Georgia has 16 olive farms, plus a few more under 5 acres. This amounts to 6,000 acres of cultivation, making Georgia’s acreage second only to California, which has four times that amount.

Olives thrive in well-drained soil and warm temperatures, but they also need cool nights – what growers call chill hours. In the southeast, that line extends from below Macon to Savannah and into South Carolina, a swatch the USDA’s plant hardiness map refers to as zone 8b. The cultivars which grow best in this region are peppery arbosana, spicy koroneiki, and arbequina, a Spanish variety which is more tolerant of cold and rich in oil.

According to Cooley Hobdy, who grows arbequina olives at Olive Orchards of Georgia in Quitman, temperature has everything to do with his yield. He claims that if it stays cold through March, he has a large crop, but “if you can put a pair of shorts on at the end of February, you ain’t going to have doodle-crap.”

Americans consume 90 million gallons of olive oil annually, more than doubling their consumption in the past two decades. Local growers claim they cannot produce enough olive oil to fill orders, displaying that consumers are increasingly seeking out this Georgia-grown crop.

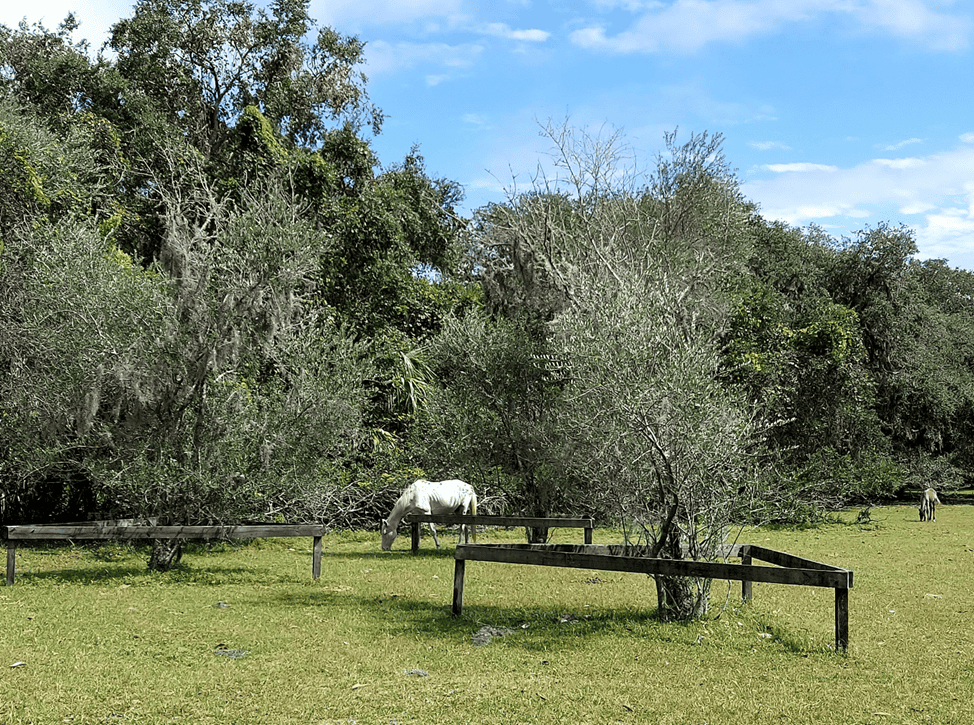

Dungeness’s three remaining olive trees no longer bear fruit; instead, they stand as lonely remnants of this area’s productive past. However, it is encouraging that they do not represent a dead art but instead signal a burgeoning industry in Southeast Georgia.

Learn more about Cumberland Island’s history and view its centuries-old olive trees up-close on our Cumberland Island Walking Tour: Haunting Ruins and Wild Horses. Also, check out our St. Marys tours such as the St. Marys Murder, Mayhem, and Martinis Walking Tour!