A Vanished Culture: The Timucua Native Americans

The date: May 1, 1562. The explorer: Jean Ribault. After a long and arduous journey, this French Huguenot officer and his troops sailed into the mouth of the St. Johns River at present-day Jacksonville, Florida, where they gratefully stepped ashore. Here they erected a column claiming this territory for France, not considering it had been inhabited for millennia by another people: the Timucua Indians. Below we delve into the history and culture of this local Native American tribe.

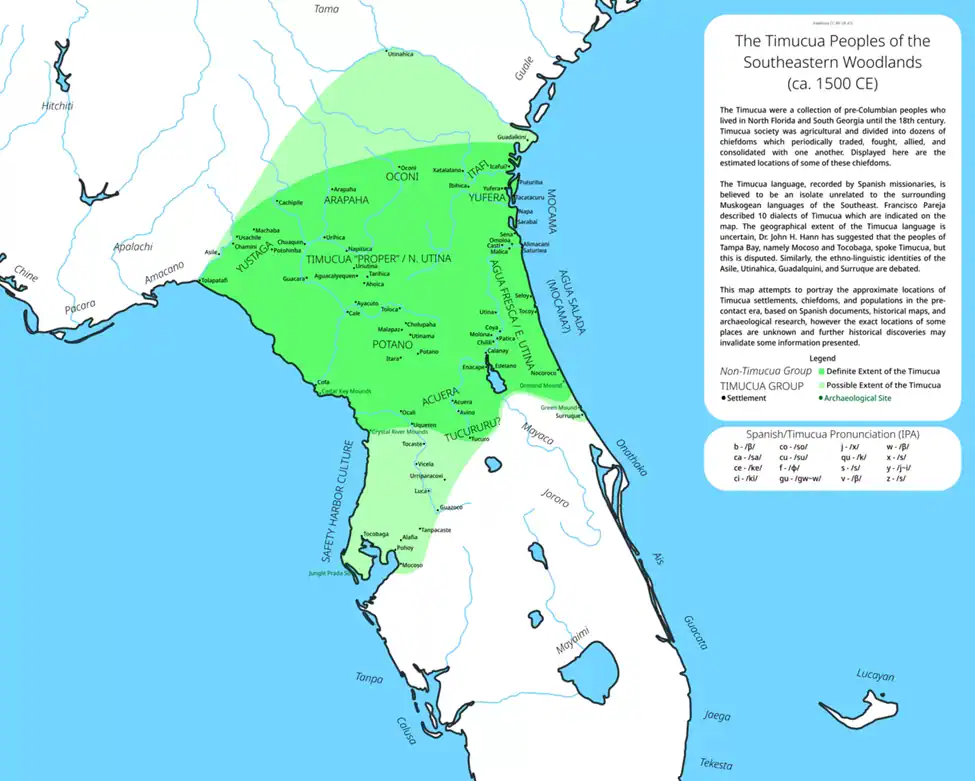

The word “Timucua” may derive from “Thimogona,” a name the chiefdom at present-day Jacksonville used to describe their enemies, the Utina, who lived inland along the St. Johns River. Eventually, thanks to Spanish usage, the term “Timucua” applied to all speakers of various dialects of the Timucua language.

These Native Americans claimed 19,200 square miles stretching from Southeast Georgia – including Cumberland Island and the St. Marys area – to North Central Florida. Here thirty-five Timucua chiefdoms, many leading thousands of people, totaled an estimated population of 200,000. These tribes did not operate as a single political unit; they occasionally formed loose political alliances but also regularly engaged in small tribal wars against their neighbors.

One of the largest and best-known Timucua groups were the Mocama, who lived in the coastal areas from St. Simons Island to south of the mouth of the St Johns River. They spoke a dialect also called Mocama, which means “Ocean.” At the time of European contact, a primary chiefdom in this area was Tacatacuru (led by Chief Tacatacuru), which was located on Cumberland Island and also controlled villages on the mainland.

The Mocama such as those at Tacatacuru usually lived in villages close to waterways and exploited the resources of marine and wetland environment such as alligators, manatees, fish, freshwater and marine shellfish, and possibly even whales. Women gathered wild fruit, palm berries, acorns, and nuts. The Timucua also consumed a highly-caffeinated black tea called cassina, brewed from the leaves of the yaupon holly tree. Only males in good status with the tribe drank this tea, which was integral to most Timucua rituals and hunts. It was believed to have purifying effects, as it caused those who consumed it to vomit immediately.

Early European explorers were shocked at the height of the Timucua, who averaged four or more inches taller than they. Timucua men wore their hair in a bun atop their heads, adding to the perception of height. Both males and females covered their dark skin with clothes made from moss or various animal skins, and they all sported extensive tattoos. Each tattoo, which the Timucua began to acquire as children, was earned through deeds and were made by poking holes in the skin and rubbing them with ash.

After the Spanish of St. Augustine defeated Jean Ribault and his troops at Fort Caroline at present-day Jacksonville, they proceeded to establish missions in each main town of the Timucua chiefdoms. They incorporated the Timucua at Tacatacuru into their mission system in 1587 with the founding of Mission San Pedro de Mocama on present-day Cumberland Island.

Contact with the French and Spanish caused the Timucua to suffer greatly from Eurasian infectious diseases. By 1595, it is believed their population was reduced from 200,000 to 50,000, with only thirteen of the original thirty-five chiefdoms remaining. By 1700, the native population fell to an estimated 1,000 through disease as well as war and slave raids carried out by Carolinian settlers and their Native American allies. The extinction of the Timucua as a tribe occurred not long after.

However, Timucua culture may not be totally dead: Aaron Broadwell, Professor of Anthropology at the University of Florida, heads a project to document and recover the Timucua lexicon. Drawing from seventeenth-century colonial documents, he has created an online dictionary and listed about 138,000 searchable Timucua definitions.

Therefore, although we may take heart that Timucua culture is being revived, it is still important that we appreciate and protect the memory of our area’s noble Native Americans. Here in Camden County, the Cumberland Island National Seashore Museum, which possesses informative historical displays, and Crooked River State Park, which boasts Timucua middens, are great places to start.

To learn about the Native American history of Southeast Georgia, join our Cumberland Island Walking Tour: Haunting Ruins and Wild Horses or our Fugitives, Fighters, and Fudge: St. Marys Walking Tour!